Restoring Forces

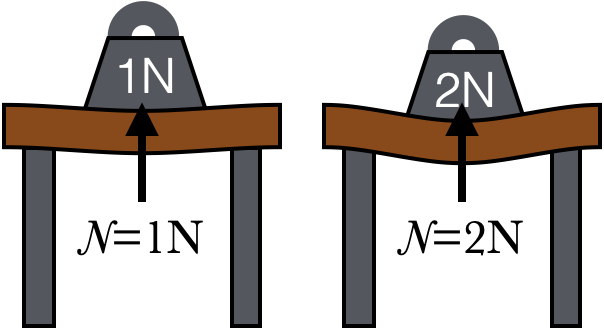

It might seem strange, if you think about it, that a table can exert any sort of push on an object sitting on it, or that it can adjust that force (within limits) to balance any other force. How does that work? Well, when a mass is placed on a table, it causes the table to bend very slightly downward, too slightly to see in most cases. Now, the tabletop is a solid, which means it likes to maintain its shape, and so there is an upward restoring force that attempts to return the tabletop to its original flat shape. A similar thing occurs when you pull on a rope, which stretches it a little bit, and the rope pulls back to try to restore its original length. Generally speaking, the greater the distortion of the object, the larger the restoring force.

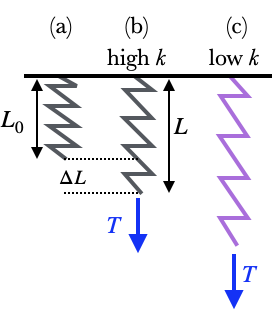

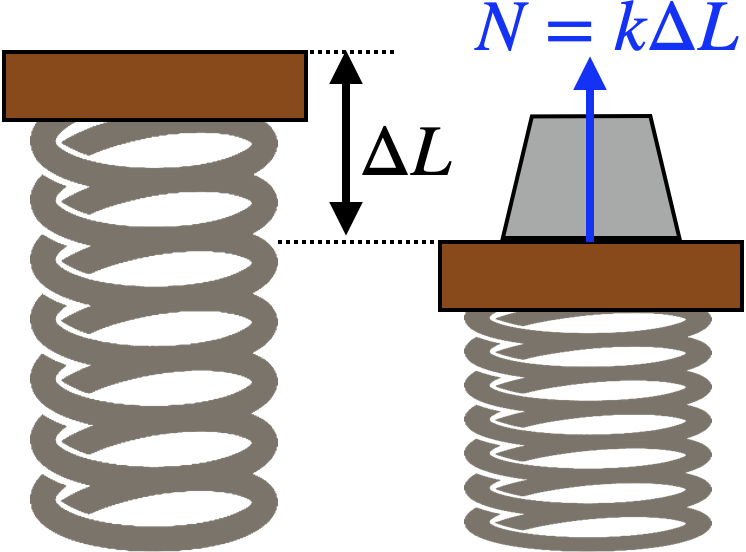

A simple model of a restoring force can be found in an ordinary spring. If a spring has a natural length $L_0$, and the spring is stretched to a length $L$, then $\Delta L = L-L_0$ is the size of the distortion, and in most cases the tension in the spring is simply proportional to this distortion, a relationship known as Hooke's Law:

where $k$ is known as the spring constant of the spring. It might be more useful to think of $k$ as the stiffness of the spring, because the larger $k$ is, the larger $F$ has to be to cause a particular distortion.

Some springs can be compressed as well as stretched; in that case, compressing a spring will result in the spring pushing back with a normal force